[Picture: Joseph, then, decides to take no vengeance... free bible images]

[For articles on the “Sabbath of K'doshim" in Hebrew, click here]

Updated on April 28, 2023Rabbi Dr. Yossi Feintuch was born in Afula and holds a Ph.D. in American history from Emory University in Atlanta. He taught American history at Ben-Gurion University.

Author of the book US Policy on Jerusalem (JCCO).

He now serves as rabbi at the Jewish Center in central Oregon. (JCCO).

* * *

In the very same breath with the Golden Rule, this weekly Torah portion -- K'doshim -- prohibits revenge-taking.

The story of Joseph helps us to understand how avoiding taking revenge is both feasible and productive despite the hurt and agony suffered by the victimized. Joseph, facing his brothers in Egypt must decide whether to remember his brothers’ cruel maltreatment, or rather see how ‘’out of the strong came forth sweetness’’ and forget his immense hurt? Indeed, he must decide whether he should remember the wrongs that he himself inflicted on them, rather than remember only the wrongs that they had inflicted on him. Joseph, then, decides to take no vengeance.

[Picture: Joseph, then, decides to take no vengeance... free bible images]

We may speculate further that not all nine brothers, upon seeing Joseph approaching them in Dothan, called in one voice unto each other, ‘’Let’s go and kill him and cast him in one of the pits’’. Perchance, these were specifically Shimon and Levi, who perpetrated earlier a huge atrocity in Schechem under the pretext of avenging the rape of their full sister Dinah in that Canaanite city by its leader's son. Even those who might try and understand the reason for their heinous revenge – the perfidious massacre of all men in Shechem – that vengeance triggered off a further ethical deterioration in the two brothers' interpersonal conduct; it culminated in their clamoring for killing their brother Joseph, simply for dreaming nightly dreams of dominance over them that he made them hear, and for being their father’s favorite son. One act of murderous revenge in Shechem led in short order to what would have been another in Dothan.

Revenge can escalate and backfire. After the Shechem massacre by his two sons, Shimon and Levi, Jacob gravely feared trouble having become ‘’odious unto the inhabitants of the land…and, I being few in number, they will gather themselves together against me and smite me, and I shall be destroyed, I, and my house’’ (Genesis 34:30). At times we too may find ourselves mulling over about what to do – take or refrain from revenge. It is proper for every person, the Rambam teaches, to overcome such a prone-to-revenge attribute. Indeed, the Rambam explains the Torah prohibition against carrying a grudge, which precedes immediately the proscription of vengeance, in that remembering proactively a wrong done to me is bound to end up with revenge. Hence, even when one is wronged by another it is incumbent on him to forget that wrong; for this is the proper way that would allow human society to continue.

When the notorious Nazi chief of the ‘’Final Solution’’, Adolf Eichmann, was sentenced to death in 1961 by an Israeli court for crimes against humanity one Shoah survivor, expressing in word what many Holocaust survivors felt: ‘’No gallows would be able to scratch the surface of the magnitude of evil that that human monster committed; even if we executed him 6 million times we would not be able to avenge what he had done or return my murdered loved ones back to life.”

Rather, revenge is for God: ‘’Mine is vengeance, requital’’ Moses lyricizes for God (Deuteronomy 32:35). Likewise, the Psalmist calls the Eternal as the ‘’God to whom vengeance belongs’’ (94:1). Perhaps this is what Joseph meant when telling his consternated brothers in Egypt who feared that he would unleash his revenge at them after Jacob’s death: ‘’ Am I in the place of God?’’ (Genesis 50:19).

Why does the Torah forbid both carrying a grudge and taking revenge? Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfrid has this reason for this prohibition: ‘’If you wish to take revenge at your enemy, then, add good attributes to yourself, and walk in straight paths; in so doing you will anyway have a revenge directed at your enemy. He will rue your good attributes, and mourn upon hearing about your good name. But if you do ugly things to him, then, your enemy will rejoice in your resultant disgrace and shame; and that would be his vengeance at you.’’

Twenty years ago, I met in Terezin a survivor of Auschwitz, Felix Kolmer, who noted in the introduction to the short book that he wrote about his ordeal: ''I saw thousands of dead, thousands who had died as a consequence of inhuman maltreatment, hunger, and illness. Possibly, I saw more than soldiers on the frontline see... In spite of that I haven't any hatred in my heart. I consider hatred to be something that deprives me of space for positive deeds, and I want, in spite of my many years, to still actively pursue such deeds." I understood right then and there why our Torah portion frowns on and forbids us from bearing a grudge and taking revenge.

[For articles on the “Sabbath of K'doshim" in Hebrew, click here]

![[Picture: Joseph, then, decides to take no vengeance... free bible images]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/יוסף-ואחיו-5.jpg)

![[Picture: Joseph, then, decides to take no vengeance... free bible images]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/יוסף-ואחיו-3.jpg)

![[In the photo: Dina's revenge - "Shimon and Levi kill the people of Nablus". Artist: Gerard Hot. The image is in the public domain]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/הנקמה-באנשי-שכם.jpg)

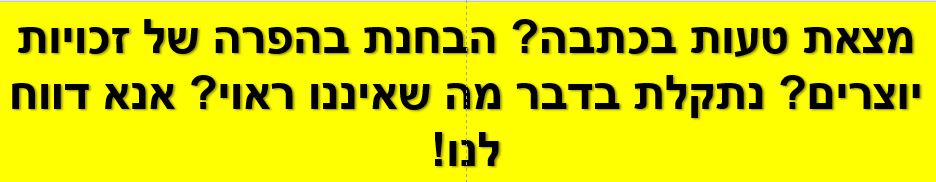

![[Picture: ‘’If you wish to take revenge at your enemy, then, add good attributes to yourself, and walk in straight paths; in so doing you will anyway have a revenge directed at your enemy. He will rue your good attributes, and mourn upon hearing about your good name. But if you do ugly things to him, then, your enemy will rejoice in your resultant disgrace and shame; and that would be his vengeance at you’’. Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and uploaded by AnnalizeArt to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/נקמה-שחור.png)